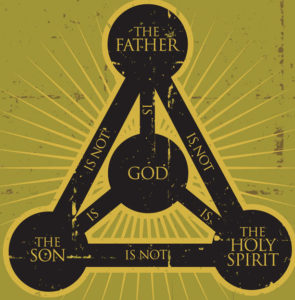

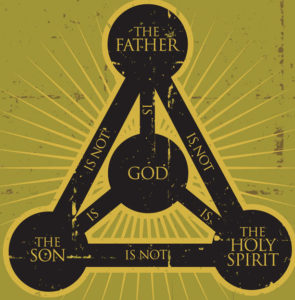

There is a theological debate going on in which Bruce Ware and Wayne Grudem have proposed an eternal subordination of the Son in the Trinity. In other words, they claim that the Son is eternally submissive to the Father in the Godhead. This is an unorthodox understanding of the relationship of the divine persons of the Godhead, akin to the ancient heresy of Arianism, because it puts the Son in a lesser, subordinate position to the Father. Leading Patristic scholars and Trinitarian experts like Michel Barnes and Lewis Ayres leave no doubt about the fact that these writers are advocating heterodoxy (false doctrine, heresy), or veering toward heresy, or at the very least using very confused language that would lead to heretical formulations regarding the Trinity. Another Trinity expert, Steven Holmes, writes that “Grudem is ready to throw the Nicene faith overboard, if only he can  keep his ‘complementarianism.’” But the doctrine of the Trinity is not the main reason for this post. It’s the “complementarianism” that moves me to write today. This new and controversial understanding of the Trinity is driven by a theological anthropology (that is, a particular view of humanity) that sees women (not wives but women per se) as subordinate in function to men (not husbands). This hierarchical anthropology is then projected onto the Trinity, in order to bolster the anthropology. That theory of humanity that views women as created by God to submit to male leadership is called complementarianism. An old friend of mine, an outstanding historical theologian and a complementarian, Carl Trueman, writes of this latest controversy about the Trinity and complementarianism:

keep his ‘complementarianism.’” But the doctrine of the Trinity is not the main reason for this post. It’s the “complementarianism” that moves me to write today. This new and controversial understanding of the Trinity is driven by a theological anthropology (that is, a particular view of humanity) that sees women (not wives but women per se) as subordinate in function to men (not husbands). This hierarchical anthropology is then projected onto the Trinity, in order to bolster the anthropology. That theory of humanity that views women as created by God to submit to male leadership is called complementarianism. An old friend of mine, an outstanding historical theologian and a complementarian, Carl Trueman, writes of this latest controversy about the Trinity and complementarianism:

“…it is sad that the desire to maintain a biblical view of complementarity has come to be synonymous with advocating not only a very 1950s American view of masculinity but now also this submission-driven teaching on the Trinity. In the long run such a tight pairing of complementarianism with this theology can only do one of two things. It will either turn complementarian evangelicals into Arians or tritheists; or it will cause orthodox believers to abandon complementarianism.”

I agree, except that I see the latter option as not only preferable, but desirable.

Orthodox believers should abandon complementarianism. Not because there is no distinction between male or female. Not because, in a general sense, men and women, husbands and wives, are not “complementary” in many ways. But precisely because they are. Women provide a much-needed complement to men…also in positions of leadership and authority. This is true in a marriage, in a household, in the church, in a business, and in society in general. And the idea that God created women to be subject to men is simply no longer credible. Women are subject to men in the Bible because, as John Calvin taught, God accommodates and adapts the Bible to the time, culture, and conventions of ancient near eastern peoples. That does not mean that God intends women to be perpetually subject to men.

The most important reason why orthodox Christians should seriously reconsider the claims of complementarianism is that it is not as biblically sound as its proponents claim. This post is not about the detailed exegetical and theological arguments to that end, but I will briefly point to Fuller Theological Seminary’s (dated but still valuable)

statement on women in ministry, and a

compelling exegetical argument by D. Heidebrecht. In sum, as Heidebrecht writes, “Reading 1 Timothy 2:9-15 within its literary context indicates that Paul is not addressing women here simply because they are women.” Carl Trueman once displayed utter disbelief that I could support the ordination of women, but I daresay he has the weaker exegetical argument. I should say that I have many friends and colleagues whom I deeply respect who are complementarians, so don’t take this as an attack. But even that is not the main reason for my post.

John Calvin, like most thinkers in the sixteenth century, did not think women should be pastors, nor, ideally, that should they be rulers. He did, however, argue that God did in fact raise up female rulers as a concession to human sin, and that the authority of female rulers is to be considered legitimate and to be obeyed. Not only that, but Calvin was

ashamed and embarrassed by John Knox, who in a

misogynist diatribe claimed that it was contrary to God’s will and the order of nature that women should hold positions of authority in government, and that female monarchs were illegitimate and should be overthrown by force of arms. Knox had very specific women in mind: Mary Queen of Scots, and Mary I of England (styled “Bloody Mary,” and not because she invented the drink). But he also claimed that women in general were “weak, frail, impatient, feeble, and foolish.” Calvin saw that Knox was undermining support for the Reformation by Protestant Queens. In fact, Calvin said that Knox was guilty of “thoughtless arrogance” by writing this inflammatory tract. Indeed, Knox ended up shooting himself in the foot and doing irreversible harm to the cause of thoroughgoing Reform in England generally when the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I ascended the throne; she despised him for his he-man woman-hating rhetoric, and extended her disdain to Geneva, to the dismay of Calvin and Theodore Beza. But while I have a compulsion to include Reformation debates in everything, this is not the main reason for this post.

Today’s complementarians would never repeat the vile things that Knox said. But too often, in my reading of many complementarians (and not all of them, mind you), the anti-female bias comes out in a patronizing way. John Piper, for example portrays women as soft and weak and vulnerable, and he even goes so far as to claim that “God made Christianity to have a masculine feel. He has ordained for the church a masculine ministry.” But this is not the Bible; this is John Piper’s projection onto the Bible of his own preferred reality. It seems to me that this is a species of idolatry, a fetishizing of masculinity, and a rather bizarre one at that. In addition, the volume Piper edited with Wayne Grudem, Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, made arguments that I found not only weak, but sometimes downright offensive (for a review of that volume by a person who had a similar assessment, start here.)

And that brings me to the main reason for this post. Complementarians are varied in their views, but increasingly, I find the whole complementarian perspective not only mistaken, but also untenable. Not in the sense that it cannot be rationally or exegetically defended, but in the sense that holding to complementarianism in the modern church is harmful to the mission and witness of the church, and therefore can no longer be held. At its worst, complementarianism leads to extremist statements like those by John Piper that women can’t hold most positions of authority over a man, or even

his deeply offensive and frankly bizarre assertion that a pastor can’t read a commentary written by a woman unless he excludes from his mind all traces of her femininity, particularly her dangerous, feminine body. This is

misogyny, pure and simple* (see this

perceptive article in Christianity Today, as well as

this blog post). I am certain John Piper does not intend it as such, but it is in fact a derogatory view of women, and it is thus ungodly, sinful, unholy, and it should be repudiated. Ultimately I judge complementarianism to be based on a simplistic reading of Scripture, but one that claims to be the “simple” and plain reading, uninfluenced by cultural assumptions. This interpretation unwittingly projects older western cultural views of women’s roles onto Pauline texts (and charges that opponents are projecting “feminism” onto the texts), while failing to distinguish incidental historical context (for example, the gender roles assumed in first century Jewish culture) from the invariable intent of Paul’s doctrine. It also minimizes the role that women actually played in Paul’s ministry.

For the complementarians, the tail is wagging the dog. To cite Steve Holmes again:

I reflect, however, that these continually-shifting arguments to defend the same conclusion start to look suspicious: by the time someone has offered four different defences of the same position, one has to wonder whether their commitment is fundamentally to the position, not to faithful theology. Judging by his essay in this book, Grudem is ready to throw the Nicene faith overboard, if only he can keep his ‘complementarianism’; other writers here are less blunt, but the same challenge may be presented. How many particular defences of a position need to be proved false before we may assert that the position itself is obviously false?

Not only my study of scripture and theology, but my pastoral experience, demonstrates to me that complementarianism is “obviously false,” to borrow Holmes’ phrase. Increasingly, this is and will be the perspective of theologians and biblical scholars.

For my own denomination, the

Christian Reformed Church in North America, I think we need to be done once and for all with the unwritten assumption among many conservatives that the

really orthodox,

really confessionally Reformed people will

of course be complementarians. Especially since zealous defenders of a male-only pulpit are now

abandoning Nicene Orthodoxy in order to advance their agenda.

This agenda is now eroding orthodoxy! Not among all complementarians (witness Carl Trueman as just one of many leading examples), but the link between keeping women in their place and orthodoxy should now be dissolved once and for all. I am orthodox and confessional, and I reject complementarianism. I did so after many years of careful, painstaking study, and much wavering in the early years of my theological education. In fact, I think that complementarianism, apart from being theologically and exegetically flawed, and impossible to practice with any real consistency, is a significant hindrance to our ministry, and particularly our witness to younger generations. It undermines our witness in a society and culture that rightly assumes that women as just as capable and gifted as men, a generation that correctly rejects subordinationist views of women as a relic from the past. Assuming that women take a back seat to men is a residue of our western history of subjugating women–women who only received the right to vote in the United States less than a century ago, and who only were declared “persons” in Canada in 1930, when the

Judicial Committee of the Imperial Privy Council overturned the Canadian Supreme Court decision that excluded women from the Senate, deciding that they were not qualified “persons.”

If God’s Word clearly and obviously forbade female leadership in the church (as complementarians insist), I would join them. But it does not. Some two decades ago, Carl Trueman, in exasperation with me, suggested that I was deliberately twisting the Bible to support the ordination of women. I remember that with a smile and don’t hold it against him. I am sure he can defend his own position. But I am doing no such thing. And I am an expert on the history of biblical interpretation, so I know what I am talking about. The only text that can be legitimately employed to argue against women in church leadership,

I Timothy 2:11-15, is not a reference to the created order; it is an

illustration–of a kind common in Jewish biblical interpretation–of how certain women in Ephesus were deceived by false teachers. The context of the Pauline letters makes it clear to me that there were women being deceived by false teachers in the church of Ephesus, and that his proscriptions on women teaching and wresting authority (αὐθεντεῖν–a very obscure word) from a man are specific to that context. There is a not a “creation ordinance” that subordinates women to men; that is an assumption and projection of western culture and tradition onto the text.

If it were a statement of the enduring created order, one would have to conclude that women are inherently more susceptible to deception (v. 14). Who in good conscience would dare make such a claim? And if this text is clear and obvious, what in the world does Paul mean (v. 15) by saying that women will be saved through bearing children? In fact, this text is very difficult to unravel. It is one of the most obscure texts in the Bible, if not

the most obscure. But what it

cannot mean is that women are spiritually inferior or inherently more susceptible to deception (which would be a degrading and patently false teaching regarding half the human race). It cannot mean that only Eve became a sinner, since Paul locates the origin of human sin in

Adam’s disobedience (

Romans 5:12-17–Paul never mentions Eve here); nor can it mean that women are saved through having children, since Paul clearly teaches that salvation comes by grace through faith. And how do these proscriptions jive with Paul’s actual practice of including women as coworkers in his ministry? I have heard many women express the feeling that Paul was down on women–but I would contend, on the contrary, that he was

revolutionary when it came to women. In

Philippians 4:2-3 the Apostle addresses two women, Euodia and Syntyche, who contended at Paul’s side in the work of the ministry (ἐν τῷ εὐαγγελίῳ συνήθλησάν μοι); Paul includes them among his coworkers in the ministry (συνεργῶν μου). It is not likely that Paul would have to urge these two women to resolve whatever dispute they had if they were not persons of influence in the church at Philippi. Priscilla and her husband Aquila are also named as Paul’s coworkers (συνεργοί) in the ministry,

Romans 16:3. Not only that, but Paul usually mentions Priscilla’s name first–a very curious reversal of convention, which indicates to me that Priscilla took the lead in the work of the ministry. Who cannot think of examples of women in their local congregation who are more invested in the work of the ministry than their husbands? And some husbands are more invested than their wives. There is no general rule.

More to the point, I am finding it increasingly difficult to minister in a context where women are not allowed to lead and to preach the Word. I find myself losing patience with the practice of excluding women, though I certainly think that a diversity of views should and must be tolerated. But the complementarian side can no longer have veto power. The implicit threat of people leaving if a congregation makes a change holds a congregation hostage, sometimes creating an atmosphere where the issue can never be discussed openly. Nor is this matter a confessional issue that would be grounds for leaving the church or fomenting a schism, as happened in the 1990s. You may not prefer to have a woman serve as an elder in your congregation, but it is not grounds for leaving or protest. The Christian Reformed Church, through careful study over many years, has amply demonstrated that there is a solid biblical-theological argument for women to serve in all offices of the church. Our seminary trains women as pastors and church leaders, and approves women as candidates for the ministry. Personally, I am getting to old to fight this battle again and again, and to listen powerlessly while women in my congregation ask me how their church could continue to exclude them from leadership in the Body of Christ. The issue became much more pointed when my own daughter looked at me with disbelief and asked how the church could have such a policy. But God does not exclude them, contrary to an older exegesis that assumed a subordinate role for women. True complementarity excludes subordination. Not only that, at my age, I do not thing I would be willing to entertain a future call to a church or ministry that does not support women in ministry, or at least allow women to serve as officebearers and to preach. Churches that exclude women from the office of deacon, moreover, have absolutely no grounds for doing so apart from tradition, and by doing so, signal that they are a church of the past, not the future. Actually, I think Christian Reformed Churches that exclude women from the office of elder also send that same signal. And, finally, it is my firm conviction that, if our churches continue to insist on this gender qualification for leadership in the church will needlessly lose all credibility with younger generations. If we lose credibility because we are preaching the gospel, that is one thing (as when the Athenians laughed at Paul over the resurrection); but younger generations are right to see that our exclusion of women is not integral to the gospel. And this will be all the more evident when it comes to the much more difficult topic of how Christians and the church should relate to homosexuals and other persons with sexual differences in a Christian and pastoral manner.

Carl Trueman wrote that the latest Trinitarian heterodoxy may have the unintended consequence of causing “orthodox believers to abandon complementarianism.” I would hope so. We need to abandon it.

*Note:

keep his ‘complementarianism.’” But the doctrine of the Trinity is not the main reason for this post. It’s the “complementarianism” that moves me to write today. This new and controversial understanding of the Trinity is driven by a theological anthropology (that is, a particular view of humanity) that sees women (not wives but women per se) as subordinate in function to men (not husbands). This hierarchical anthropology is then projected onto the Trinity, in order to bolster the anthropology. That theory of humanity that views women as created by God to submit to male leadership is called complementarianism. An old friend of mine, an outstanding historical theologian and a complementarian, Carl Trueman, writes of this latest controversy about the Trinity and complementarianism:

keep his ‘complementarianism.’” But the doctrine of the Trinity is not the main reason for this post. It’s the “complementarianism” that moves me to write today. This new and controversial understanding of the Trinity is driven by a theological anthropology (that is, a particular view of humanity) that sees women (not wives but women per se) as subordinate in function to men (not husbands). This hierarchical anthropology is then projected onto the Trinity, in order to bolster the anthropology. That theory of humanity that views women as created by God to submit to male leadership is called complementarianism. An old friend of mine, an outstanding historical theologian and a complementarian, Carl Trueman, writes of this latest controversy about the Trinity and complementarianism: