A Case for the Ordination of Women to the Ministry,

Part 1.

I have made it known in a previous post that I can no longer defend or support with any enthusiasm the option to bar women from holding the ordained offices of elder and pastor in the church. I also feel that it is crucial for Christian Reformed churches to get past this issue, over twenty years after our Synod made its final decision on the matter (1995), in order for us to speak credibly to the current generation. In other words, I am convinced that continuing to bar women from leadership in the church will harm our witness and growth and our work of making disciples. It’s not that we should cave in to the world’s standards; it’s that people inside and outside of the church can see when our standards have gone awry. And they have gone awry in this case, as I intend to demonstrate. I am convinced that churches that want to grow through evangelism (and not merely attract Christians from other churches) need to move beyond this relic of a past era. Because in reserving ecclesiastical office for men only, we are not clinging to biblical teaching, but to a very human, very culturally conditioned understanding of gender roles.

In recent times, the debate over whether women should be ordained as elders and pastors has been framed, rather badly I think, by the terms egalitarian and complementarian. The term egalitarian means “supporting equality.” It asserts that men and women are equal. Yet most complementarians would agree that women and men are equal, but dispute the assertion that this equality means that women and men have the same roles in the church. However, some (certainly not all) complementarians also seriously undermine the equality of women in ways that are shockingly sexist and misogynist. One sees this particularly in the remarks of John Piper, who asserts that “God has given Christianity a masculine feel,” and that “the fullest flourishing of women and men takes place in churches and families where Christianity has this God-ordained, masculine feel. For the sake of the glory of women, and for the sake of the security and joy of children, God has made Christianity to have a masculine feel. He has ordained for the church a masculine ministry.” Piper asserts that God calls men to take the initiative spiritually, and women come alongside in a supporting role. Throughout this sermon, Piper paints a picture of women as weak, fragile, vulnerable, soft, and in need of protection by brawny, muscular, tough-skinned men, who can valiantly and gallantly teach hard truths like the doctrine of Hell and not burden the delicate ladies with the task of teaching these difficult topics. But this “masculine ministry” is not Biblical teaching; this is the “muscular Christianity” of the Victorian era. It is a view of women and men shaped by the romantic notions of a bygone age. And it is condescending to women. It is also harmful to men, who are made to feel like they have to be tough and strong, and also extroverted in terms of spiritual leadership. It is, to use Martin Luther’s terminology, a kind of theology of glory that leaves little room for suffering and weakness.

In recent times, the debate over whether women should be ordained as elders and pastors has been framed, rather badly I think, by the terms egalitarian and complementarian. The term egalitarian means “supporting equality.” It asserts that men and women are equal. Yet most complementarians would agree that women and men are equal, but dispute the assertion that this equality means that women and men have the same roles in the church. However, some (certainly not all) complementarians also seriously undermine the equality of women in ways that are shockingly sexist and misogynist. One sees this particularly in the remarks of John Piper, who asserts that “God has given Christianity a masculine feel,” and that “the fullest flourishing of women and men takes place in churches and families where Christianity has this God-ordained, masculine feel. For the sake of the glory of women, and for the sake of the security and joy of children, God has made Christianity to have a masculine feel. He has ordained for the church a masculine ministry.” Piper asserts that God calls men to take the initiative spiritually, and women come alongside in a supporting role. Throughout this sermon, Piper paints a picture of women as weak, fragile, vulnerable, soft, and in need of protection by brawny, muscular, tough-skinned men, who can valiantly and gallantly teach hard truths like the doctrine of Hell and not burden the delicate ladies with the task of teaching these difficult topics. But this “masculine ministry” is not Biblical teaching; this is the “muscular Christianity” of the Victorian era. It is a view of women and men shaped by the romantic notions of a bygone age. And it is condescending to women. It is also harmful to men, who are made to feel like they have to be tough and strong, and also extroverted in terms of spiritual leadership. It is, to use Martin Luther’s terminology, a kind of theology of glory that leaves little room for suffering and weakness.

The opposite term, complementarian, also leaves a lot to be desired. It means that men and women are different yet complementary. Aristophanes, the Greek comedian, tells a story in Plato’s Symposium, about how human beings originally had two heads, and double all the normal body parts, but when these creatures got too prideful, Zeus blasted them in two, and now men and women only feel whole and complete when they find their (literal) “other half.” I think it is clear that egalitarians can also affirm that women and men are complementary in a general sense. Egalitarians do not want to erase or ignore gender distinctions. But they also, rightly, shy away from making blanket statements about the qualities of women and men, because these are not universal, and experience teaches us this. We should not deal in stereotypes. In fact, one can argue that it is precisely the differences that men and women bring to leadership that makes it crucial to employ the experiences and voices of women in the leadership, pastoral care, and preaching of the church. I can testify that my own preaching voice has been strongly shaped by female pastors, particularly by the homiletical art of Barbara Brown Taylor, and the rhetorical and contextualizing skill of Fleming Rutledge.

Clear and Plain?

I recently heard again the common refrain that the Bible is clear that women should not hold positions of authority in the church; the Bible’s plain teaching is that pastors and elders should be men. This clarity has been highly exaggerated. In fact, the argument is built on a foundation of sand.

The main passage that is cited to bar women from preaching or exercising the office of pastor and elder (as defined in the Reformed and Presbyterian traditions) is 1 Timothy 2:11-15. This is the number one passage that people cite to make the claim that the Bible is so clear and obvious and plain when it prohibits women serving as preachers and elders. But in fact, this is one of the most obscure and difficult passages in the entire Bible. It is not at all clear. The passage reads as follows:

1 Timothy 2:11–15 (NIV)

11 A woman should learn in quietness and full submission. 12 I do not permit a woman to teach or to assume authority over a man; she must be quiet. 13 For Adam was formed first, then Eve. 14 And Adam was not the one deceived; it was the woman who was deceived and became a sinner. 15 But women will be saved through childbearing—if they continue in faith, love and holiness with propriety.

So, let’s ask a few obvious questions about this passage.

- What does Paul mean when he says “women will be saved through childbearing”? Whatever he means, the one thing he most certainly cannot mean is that…women will be saved through childbearing! Paul often and emphatically teaches that persons are saved by grace through faith. Women are not saved in a different method than men. There are not separate male and female salvation tracks. And what about single women, and women unable to have children: Can they be saved? And what about continuing “in faith, love and holiness with propriety”–is this what saves a person? One’s good works? One’s tranquil and serene lifestyle? Clearly not.

- And do we really want to say that women are by nature more susceptible to deception? And that God created women this way? That seems to be the implication of verse 14, or at least that seems to be the meaning if (as complementarians insist) this is a reference to an enduring and unchangeable “creation order.” But if it is, then the Bible really does teach that women are more susceptible to deception, and men less so. But this is false, sexist, and chauvinistic… clearly so. It implies that women are intellectually and morally inferior, and that is theologically unacceptable. Such an assertion impugns God’s character as Creator. Is Paul a sexist? Is God? But in fact, Paul is not referring to some supposed creation order that endures through eternity; he is using an illustration from scripture. Just like Eve was deceived and fell into sin, some women in the Ephesian church have been deceived by false teachers who have been taking advantage of them, and Paul prohibits these women from teaching the false doctrine they have imbibed. Paul does something similar in Galatians 4:24-27, where he takes the story Abraham, Sarah, and Hagar from Genesis and interprets it allegorically, that is, changing the meaning of the literal events to make a spiritual application.

- And how far does one take this prohibition of teaching by women? Can women teach

Sunday school or catechism or a youth group lesson or lead a Bible study that includes men? Can they teach boys the faith? The preacher Timothy seems to have learned the faith from two important women in his life, his grandmother Lois and his mother Eunice (2 Tim. 1:5, 3:14-15). Can a woman study academic theology or biblical studies, and in turn, teach men in a seminary? Like leading Cambridge University theologian Sarah Coakley? Or like theologian Mary Vandenberg and biblical scholars Amanda Benckhuysen and Sarah Schreiber in the Christian Reformed Church’s own denominational seminary? Or my friend Suzanne McDonald at Western Theological Seminary? Or is the fact that these scholars are women teaching men theology an act of disobedience, and dishonoring to God? Can a man read a biblical commentary written by a woman without committing sin? (John Piper, again, is not so sure). Can a woman be the editor of North America’s leading evangelical magazine? Clearly, this implies having a role in the spiritual instruction of men. Yet how many of us would object to Katelyn Beaty‘s role as managing editor of Christianity Today? (Especially if you know that she’s a Calvin College alumna!) If there is one thing that’s clear, it’s that we are exceptionally inconsistent in applying this supposed principle.

Sunday school or catechism or a youth group lesson or lead a Bible study that includes men? Can they teach boys the faith? The preacher Timothy seems to have learned the faith from two important women in his life, his grandmother Lois and his mother Eunice (2 Tim. 1:5, 3:14-15). Can a woman study academic theology or biblical studies, and in turn, teach men in a seminary? Like leading Cambridge University theologian Sarah Coakley? Or like theologian Mary Vandenberg and biblical scholars Amanda Benckhuysen and Sarah Schreiber in the Christian Reformed Church’s own denominational seminary? Or my friend Suzanne McDonald at Western Theological Seminary? Or is the fact that these scholars are women teaching men theology an act of disobedience, and dishonoring to God? Can a man read a biblical commentary written by a woman without committing sin? (John Piper, again, is not so sure). Can a woman be the editor of North America’s leading evangelical magazine? Clearly, this implies having a role in the spiritual instruction of men. Yet how many of us would object to Katelyn Beaty‘s role as managing editor of Christianity Today? (Especially if you know that she’s a Calvin College alumna!) If there is one thing that’s clear, it’s that we are exceptionally inconsistent in applying this supposed principle.

A Rare and Unclear Term

Another thing that is not entirely plain or clear is the meaning of the word that the NIV translates as “assume authority.” It is the Greek verb αῦθεντεῖν (authentein), and it is what we call a hapax legomenon, a word that appears only once in the New Testament. This means that it is exceedingly difficult to figure out exactly what Paul means by this term, and many scholars have written articles about its possible meanings. The Authorized (King James) Version translates it: “usurp authority” over a man, that is, to seize authority that rightfully belongs to someone else, by illegitimate means. The most common Greek dictionary defines it as: “to have authority, or domineer over someone.” So just restricting ourselves to this range of meaning, the word can convey either that Paul does not permit a woman to have any authority over a man (presumably limited to the sphere of the church, since a mother has authority over her male sons according to God’s law in the fifth commandment), or that Paul is prohibiting women from undermining legitimate authority and presuming to hijack and replace that legitimate authority.

In addition, Paul prohibits women from teaching. But how far does this go? Is it restricted to teaching children? Remember Priscilla and Aquilla, who worked alongside Paul in his ministry? Paul generally names the wife Priscilla first, which is unusual and noteworthy; he calls them his “co-workers” in the ministry of evangelism and planting churches. This wife-husband pair discipled Apollos (the future evangelist) in the Christian faith, that is, they both taught Apollos the way of Christ. We read about this in Acts 18:26–another instance where Priscilla’s name is mentioned first, which I think implies that she took the lead. And to be realistic, we know of couples where the wife is more outgoing and evangelistic than the husband and more of a student and teacher than her spouse. And we don’t generally object to this, because we know that God gifts persons differently. We know that some people are more introverted, others more extroverted, and this difference crosses gender lines.

So, to come back to the important question: Is Paul’s prohibition against women teaching in the church all that clear? Did he even follow it universally himself? And what grounds are there for restricting this teaching prohibition to the pulpit? If it is, in fact, a universal principle for all times and places, we may need to rethink women as chairs of committees, women as Sunday School and Catechism teachers, women as mentors and disciplers, and women as youth group leaders who disciple young men. The answer to the question of precisely how to restrict women’s roles will not be found in the Bible. I think that we have traditionally focused on the pulpit and to the offices of the church as a male-only domain because of our very western and male-centered cultural assumptions about the roles of women in society. This would be ironic because the usual accusation one hears is that advocates for women in the ministry are taking their cues from modern culture and not the Scriptures, but I think the opposite can just as easily be the case. Opponents of women in ministry are just as shaped by cultural assumptions and biases as any other readers of Scripture. In fact, it is precisely because I hold to the Reformed principle of scripture alone (sola scriptura) as the sole authority for church practice and teaching, that I come to a different conclusion when I study the important texts, and especially when I study them in their Biblical and cultural context.

…the usual accusation is that advocates for women in ministry are taking their cues from modern culture and not the Scriptures, but I think the opposite can just as easily be the case. Opponents of women in ministry are just as shaped by cultural assumptions and biases as any other readers of Scripture.

In the next post, I will discuss that biblical and historical context, and hopefully shed some light on this very difficult and obscure text, and perhaps make it less difficult, not so obscure, if not downright clear.

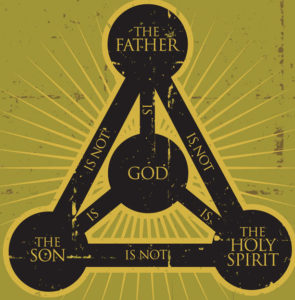

keep his ‘complementarianism.’” But the doctrine of the Trinity is not the main reason for this post. It’s the “complementarianism” that moves me to write today. This new and controversial understanding of the Trinity is driven by a theological anthropology (that is, a particular view of humanity) that sees women (not wives but women per se) as subordinate in function to men (not husbands). This hierarchical anthropology is then projected onto the Trinity, in order to bolster the anthropology. That theory of humanity that views women as created by God to submit to male leadership is called complementarianism. An old friend of mine, an outstanding historical theologian and a complementarian, Carl Trueman,

keep his ‘complementarianism.’” But the doctrine of the Trinity is not the main reason for this post. It’s the “complementarianism” that moves me to write today. This new and controversial understanding of the Trinity is driven by a theological anthropology (that is, a particular view of humanity) that sees women (not wives but women per se) as subordinate in function to men (not husbands). This hierarchical anthropology is then projected onto the Trinity, in order to bolster the anthropology. That theory of humanity that views women as created by God to submit to male leadership is called complementarianism. An old friend of mine, an outstanding historical theologian and a complementarian, Carl Trueman,