I’m reading Calvin’s Institutes, a new translation of the 1541 French edition, for a book review for Calvin Theological Journal. It’s a good opportunity to re-read the Institutes in a different form than the one I read in college a few decades ago. I just came across Calvin’s discussion, in the early pages of the first chapter, of the “seed of religion,” that sense of the divine that is in all people, no matter what their culture or civilization may be. All people are religious, Calvin says. And it’s a good reminder that “religion” is not a bad word, contrary to what we hear from many Christian writers, as well as many non-Christian writers. Religion really means: a person’s sense or perspective on the big picture. Religion has to do with what’s ultimately important in life, and in your life. Religion has to do with what drives you in life, what life is about, what life is for, what life means. For many, religion is about having a good life, avoiding pain, and trying to be as prosperous as possible, and trying not to hurt anyone in the process. For some, religion is about pretending you’re not religious, and claiming, instead, to be “spiritual.” For others, their religion is a profound faith in science and technology, together with the hope that humanity will evolve and progress and just get better and better. (It’s a good idea for those whose religion is scientific progress to avoid the reading of history, otherwise they might have a crisis of faith). I heard recently of a new science cult which adamantly denies that it is a religious movement, even as its followers zealously promote its utopian view of the future where humans and machines will merge. Sounds like evangelism to me. Sounds like a vision of heaven…or hell.

The Christian Religion, as Calvin rightly and boldly calls our faith, finds the meaning of human life in the story of God the Creator, who is also God the Savior in Jesus Christ, and God the Healer and Restorer, the Holy Spirit. This is the story of God who draws his broken and rebellious people, his runaway sons and daughters, back into relationship with him. “Religion” should never be contrasted with “relationship,” as popular Christian authors constantly do, pretending that they’ve actually solved some kind of problem, or said something profound. The catchphrase “personal relationship with Jesus” is too vague, too individualistic, to small to sustain the weight of what God is really doing in the world. He is transforming the whole creation in Christ. He is reconciling the world to himself. Of course he does this by transforming individual hearts and souls and lives, but he always does this in community. Richard Mouw of Fuller Seminary recently wrote an article for Christianity Today about the proper balance between the individual and the community in Christian consciousness. While liberal churches ignore individual conversion and transformation, Evangelical churches focus far too exclusively on the individual. He writes, “We evangelicals never downplay the importance of individuals—as individuals—coming to a saving faith in Jesus Christ. We never say that an individual’s very personal relationship to God is not important. What we do say is that individual salvation is not enough.”

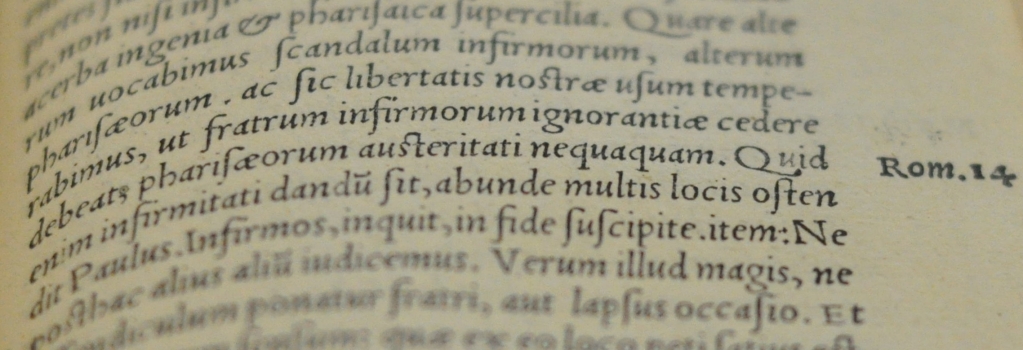

Then Calvin says something that suprised me. I’m sure I read it many years ago, but I had forgotten. Calvin speaks of the universal sense of divinity, the awareness that there is a God in all people. Then he writes, “That is why it is false to say (as some do) that religion was long ago contrived by the art and clever ruse of a few people, in order to control the naive populace in decency even though the ones who were urging others to honor God had no idea of the divine. I certainly admit that some delicate and deceitful people among the pagans have forged many things in religion to make naive people afraid and cause them scruples, so that they would be more obedient and easier to order around; but they would not have succeeded in this if people’s spirits had not first been fixed on the firm persuasion that there is a God. From that source came the whole inclination to believe what was said about religion.” (Institutes of the Christian Religion, 1541 French Edition, tr. Elsie McKee, p. 26). Calvin wrote this 300 years before Karl Marx claimed that religion was just a tool used by the powerful to control the weak. Calvin, by contrast, says that while religion might be misused in this way, such abuse of religion does not explain the universal prevalence of religion. Marxism itself was a secularized religion, complete with its own world-view, values, and vision of a utopian socialist future. Its interesting that 500 years after Calvin’s birth, the same issues are being debated. Today we have Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins touting a new atheism, and a return to “reason,” without the slightest clue that their “new” atheism is really quite old, and–even more embarrasing–it is itself a religion, a view of how things should be, an argument about the meaning of life (or lack thereof). Not only that, but their arguments against belief in God can’t even hold enough water to spawn a newly-evolved life form. Disbelief takes just as much faith as belief; the atheist is just as religious as the believer.

Sandy attended the

Sandy attended the